Category: Books

-

The Comic Book As Biography

There’s a good article in today’s Guardian about Fun Home, the graphic novel written and drawn by Alison Bechdel. The tagline to the title is "A Family Tragicomic" – a punningly apt description, for it’s a biography of her family, in particular her father – dead by age 44, done in the form of a graphic novel.It turns out, according to the Guardian article, that the success of the book has been something of a mixed blessing to Bechdel, who created the book almost as a way to write about issues beneath the surface in her childhood. She, and her family, was totally unprepared for the level of attention that the book has created. I found the book surprisingly moving. It is certainly worth getting hold of a copy. Fun Home takes its place on my bookshelves alongside three other examples of this genre, biography told via the format of the graphic novel. Art Speigelman’s Maus I and Maus II, and Raymond Briggs’ Ethel and Ernest. The two Maus books deal with the life of Speigelman’s father, Vladek, and his life as a Jew under the Nazi regime. They are, as you can imagine, quite harrowing to read, but worth it. Briggs’ Ethel and Ernest spans almost the same period as Maus, but this time we are far away from the death camps of Auschwitz. Briggs tells the story of his parents, a pair of decent, ordinary people. This book is the one that invariably brings tears to my eyes each time I read it. An apparently simple tale about simple folk, told by a master storyteller and illustrator. The result is almost unbearably moving. My favourite of the bunch. -

Murder In Amsterdam – Part II

Recently, I mentioned the new book by Ian Buruma. I bought a copy and have just finished it. Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo Van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance is every bit as good as I hoped for. Buruma interviewed a wide range of people in Dutch society for the book, from all sides and walks of life. The result is a cross-section of voices that illuminate the scene and show that there are many strands of attitude and belief.

Buruma doesn’t have any easy answers for how Dutch society can accommodate these many strands, although he does comment on some of the people he interviews. He also paints portraits in his words of some of the players that he could not interview: Pim Fortuyn and his murderer, Volkert van der Graaf; Theo van Gogh and his murderer, Mohammed Bouyeri. Buruma shows that the two murderers shared attitudes in common:

It is a characteristic of Calvinism to hold moral principles too rigidly, and this might be considered a vice as well as a virtue of the Dutch. It played a part in the makeup of Van der Graaf, as well as Mohammed Bouyeri, and even Theo van Gogh. The two killings, of Van Gogh and Fortuyn, were principled murders.And, says Buruma, committed by a pair of society’s losers. He mentions the psychiatric report on Bouyeri, prepared for his trial:

[Professor Ruud] Peter’s report, prepared for the court, makes for strange reading, because he attempts to find coherence in these violent ravings [in Bouyeri’s writings] where often there is none. “Ideological and religious development” is a rather grand description of Mohammed’s thinking. But the report is worth studying nontheless, not so much for what it says about Islam, but for what it says about the revolutionary fantasies of a confused and very resentful young man. These are not so different from the fantasies of other confused and resentful young men in the past. You can find them in the novels of Dostoyevsky or Joseph Conrad, desperadoes who imagine themselves as part of a small elite, blessed with moral purity, surrounded by a world of evil. They are obsessed with the idea of violent death as a divinely inspired cleansing agent of worldly corruption.In a weird sort of way, I am reminded of the ending of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, where the hero, Sam Lowry, retreats into madness as a way of escaping from the society in which he lives. The last words of the film are Mr. Helpmann, the Minister of Information, saying to Lowry’s friend and torturer: “I think we’ve lost him“.

In a perverse parallel, it seems to me that Bouyeri has retreated into his world of religious zealotry from which he will never escape. He sits in his prison cell surrounded by his holy books and continues to dream his revolutionary fantasies. I think we’ve lost him. But we cannot afford to lose more like him.

-

Thy Will Be Done

Kingdom Come is the latest novel by the great J. G. Ballard. It’s yet another of his dystopian visions of our society, very much following in the footsteps of Cocaine Nights, Super-Cannes and Millennium People. Actually, much of his later writing strikes me as either skirting dystopia or plunging headlong into it and splashing about gleefully. By contrast, some of his early writing is positively elegaic; the short story The Garden of Time, for example. Written in 1963, and read by me in the same year, it’s a story that has stuck with me ever since. It’s worth tracking down – it was described by Brian Aldiss as ‘a wonderful fantasy, the most magical of metaphors’, and by Anthony Burgess as ‘one of the most beautiful stories of the world canon of short fiction’. It can be found in Ballard’s first collection of short stories, originally titled The Fourth-Dimensional Nightmare, but reissued under Ballard’s preferred title of The Voices of Time.Now, thanks to a tip in BLDBLOG, I’ve found a long and interesting interview with the man himself. It’s worth reading. -

Marjane Satrapi

I’d not heard of her before, but this interview with Marjane Satrapi has piqued my interest. Her book Persepolis looks like another for the "want" list.(hat tip to Not Saussure for the link) -

Jaw-Dropping

I’ve mentioned the Online Books Page before. Then, it was in the context of a Lucky Dip – you never quite knew what you were going to come up with. Well, of course, sometimes you reach in and pull out something that is not pleasant at all. Today, for example, I felt as though I’d reached in and pulled out a large steaming turd. The library index contains a reference to a book published in 1907: Robert W. Shufeldt’s The Negro, A Menace To American Civilization. Jaw-dropping racism that quite takes the breath away. The book has been collected online in a web site that seems to have other, er, interesting treatises. Enter at your own risk. -

Who’s Deluded Here?

Richard Dawkins’ new book: The God Delusion is out. And the reviews are appearing. First up is a very negative review in Prospect Magazine by Andrew Brown (followed by a further negative ramble about the review in the Guardian’s Comment is Free). However, his dyspeptic review is countered by Joan Bakewell’s review of Dawkins’ book in today’s Guardian. She, by contrast, finds that "Dawkins gives it to believers with both barrels and cheers him on".I’ll make my own mind up on the book once I’ve read it. I’m currently awaiting it to drop into the postbox. But I can confidently predict that my reaction is more likely to be closer to that of Bakewell’s rather than Brown’s. -

Murder In Amsterdam

Here’s a book review that makes me want to go out and buy the book immediately (or, this being the Internet age, go to Amazon and click). The book in question is Ian Buruma’s Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance.The book gets a glowing review. Interesting that Buruma is another observer who sees characters such as Bouyeri (van Gogh’s murderer) as self-loathing losers. As the reviewer (Claire Berlinski) writes:Buruma finds him virtually the embodiment of the archetype described by the German writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger as "the radical loser": young, talentless, self-pitying; a man whose loathing of himself could be converted with only scant coaxing into a violent loathing of others. (This character was also foreshadowed, of course, over and over again, in Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground.) Bouyeri was pudgy. He was no good at sports. Dutch women snubbed him. His parents, bewildered immigrants from a remote village in the Moroccan Rif mountains, appeared to him whipped, subservient, humiliated.The review itself is worth reading – it looks as if Buruma has captured aspects of multicultural Dutch society and pinned them like butterflies onto his specimen board for us to gaze at and ponder on. They are not always a pleasant sight. And Buruma apparently offers no solutions. But understanding what we are dealing with is the first step in the right direction. -

Lucky Dip

One web site I keep an eye on is The Online Books Page – a web site that lists the titles of online books that have been added to an index maintained at the University of Pennsylvania. The index contains over 25,000 books so far.

The books themselves are a real mixture, some are real gems and others are, well, either dull or frankly bizarre.

Take the titles posted on the 5th September 2006, for example. There are complete online versions of some serious biology texts (e.g. Genomes, published in 2002). Then there are two books (Mental Chemistry and The Master Key System), both written by Charles F. Haanel in (I think) the 1920s. Mental Chemistry is unwittingly hilarious for its often pompous and overblown rhetoric, but with The Master Key System we cross over into woo-woo land starting at the third paragraph of the introduction:

Humanity ardently seeks "The Truth" and explores every avenue to it. In this process it has produced a special literature, which ranges the whole gamut of thought from the trivial to the sublime – up from Divination, through all the Philosophies, to the final lofty Truth of "The Master Key".

The "Master Key" is here given to the world as a means of tapping the great Cosmic Intelligence and attracting from it that which corresponds to the ambitions, and aspirations of each reader.

I also love the way the Psi Tek web site introduces the book:

The Master Key System is simply one of the finest studies in personal power, metaphysics, and prosperity consciousness ever written.

Covering everything from how to create abundance and wealth to how to get healthy, Charles F Haanel leaves no stone unturned. With precision, he elucidates on each topic with logic and rigor that not only leaves you feeling good, but also thinking good. The book was banned by the Church in 1933 and has been hidden away for decades.

Rumor has it that while he was attending Harvard University, Bill Gates discovered and read The Master Key System. It was this book that inspired Bill Gates to drop out of the University and pursue his dream of "a computer on every desktop." You probably know the results. . .

I just love that "Rumor has it…" touch, don’t you? And why the Church (er, which one?) would want to ban this pile of old codswallop is simply one of life’s great mysteries…

-

Hell Hath No Fury…

…Like a biographer scorned. So the biographer Bevis Hillier was the person who wrote the fake Betjeman letter. He did it as an act of revenge on his rival, A. N. Wilson, who encroached on his territory by writing a biography of Betjeman as well, and who also disparaged Hillier’s work in a scathing review.Wilson failed to appreciate that the fake love letter supposedly penned by Betjeman was sent to him by "Eve de Harben" (an anagram of "ever been had"), and that the first letters of each line in the letter spelt out "A. N. Wilson is a shit". Not only did he fail to spot it, but he trumpeted the discovery of a hitherto unknown love letter in his biography.Game, set and match to Hillier, I think. -

And This Year’s Winners Are…

Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a writer whose name has become synonymous with bad prose. He gives his name to the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, which seeks to identify the worst examples of writing of the year. This year’s contest winners have just been announced.I particularly like the winner of the Vile Puns section (having a weakness for puns):As Johann looked out across the verdant Iowa River valley, and beyond to the low hills capped by the massive refrigerator manufacturing plant, he reminisced on the history of the great enterprise from its early days, when he and three other young men, all of differing backgrounds, had only their dream of bringing refrigeration to America’s heartland to sustain them, to the present day, where they had become the Midwest’s foremost group of refrigerator magnates.And I quite like this entry, which got a dishonourable mention:Hardly a day passed without poor Matilda looking back on her life and ruing that fateful day she decided that to cut her toenails with her father’s scythe to make up that extra four minutes she had wasted listening to "Muskrat Love" by the Captain & Tennille. -

Flurb

Ooh, a new web-based publishing venture for Science Fiction and Fantasy writing! It could be interesting… -

Book Review: Murder in Samarkand

The Sharpener has a review of Craig Murray’s book Murder in Samarkand. While I have a copy of this in my library, I haven’t yet got around to reading it. This review would seem to suggest that I should increase the priority, tout de suite. -

Lucky Dip

One of the wonders of the web is the fact that many old books, whose copyright has lapsed, are being put online. I often find myself looking through the contents of The Online Books Page in the hope of striking lucky. Today for example, I see that a PDF version of an astronomy book published in 1900 is now available: Essays in Astronomy by Ball, Harkness, Herschel, Huggins, Laplace, Mitchel, Proctor, Schiparelli, and Others (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1900). This is terrific stuff. For example, there’s an essay by Lord Kelvin setting out what he can surmise, using the best available scientific knowledge of the time, about the age of the sun. He concludes:It seems, therefore, on the whole most probable that the sun has not illuminated the earth for 100,000,000 years, and almost certain that he has not done so for 500,000,000 years. As for the future, we may say, with equal certainty, that inhabitants of the earth can not continue to enjoy the light and heat essential to their life for many million years longer unless sources now unknown to us are prepared in the great storehouse of creation.Now, Lord Kelvin was a great scientist, who did important research in physics, and in particular, thermodynamics. Yet, science at that stage was only just begininng to uncover the workings of nuclear physics, and hence the mechanisms at work in the sun were unknown to him. His conclusions, made on the best evidence available to him at the time, were ultimately wrong.There’s also an essay by Giovanni Schiaparelli on the planet Mars. The translation, from the original Italian, uses the word "canals" instead of Schiaparelli’s intended word "channels". Thus was a whole myth seeded about there being canals on Mars.20-20 hindsight is, of course, easy in retrospect. But then again these essays also show the scientific method in action. Working with the data available to them at the time, they formulated theories that made sense for their time. Subsequent new findings allowed new theories to arise that fitted the known facts better, and science moved on. -

Stiff

I’ve just finished reading Stiff, by Mary Roach. It’s a delightful book (no, really), all about human cadavers. Roach writes with a wry wit, possibly in part as a way to cope with the subject matter at hand, but she does it very well. She opens her book with a bang, describing the scene of forty heads (each "about the same size and weight as a roaster chicken") sitting in individual roasting pans awaiting their turn to be practiced on by plastic surgeons attending a facial anatomy and face lift refresher course. Subsequent chapters are devoted to cheery topics such as body-snatching, human decay, crash test dummies, crucifixion experiments, head transplants, cannibalism and such like.One chapter gives the back story of the work of Susanne Wiigh-Masak, who is turning dead bodies into compost (and good luck to her, I say; it seems an eminently practical thing to do). When Roach met her, Wiigh-Masak was still trying to get her ideas accepted, but as I reported last year, it does seem as though she has now won over the parish administrators of Jönköping.In the pages of Roach’s book, we meet not just sensible people and dedicated professionals, but also (in Roach’s words) a number of wacks. Somewhat unsurprisingly, one of them (a Dr. Pierre Barbet) was devoted to proving the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin. This involved crucifying dead people and he spent many happy hours banging in the nails.I was also delighted to see the appearance in Stiff of another "wack" – the simply wonderful, and completely barking, General Albert N Stubblebine III. Roach can’t resist retelling the story of one of General Stubblebine’s experiments in remote viewing, and who could blame her. For more on the General, and his colleagues in one of the wilder shores of the US Army, I thoroughly recommend Jon Ronson’s The Men Who Stare At Goats. Ronson opens his book by describing the true story of the scene where General Stubblebine believes that he can go to the office next door by simply walking through the wall. Yep, you read that correctly. Ronson’s book is by turns both hilarious and chilling, and its pages are liberally sprinkled by a cast of characters who are either deluded or certifiably insane. The really bothersome part is that Ronson’s book is ostensibly not a work of fiction. These people are real.So there you go, two book recommendations for the price of one. Both are excellent. -

MRDA

Fareena Alam writes a nasty and spiteful review of Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s book The Caged Virgin in The New Statesman. Sample: "Hirsi Ali, a woman who has built her career on portraying herself as a victim". Er, no, Ms. Alam, Hirsi Ali certainly does not portray herself as a victim, quite the opposite in fact.Alam relates, with relish, the story of the Dutch TV documentary that in May this year led to "the Hirsi Ali affair", whilst neglecting to point out that the fact that Hirsi Ali had lied to get asylum was public knowledge back in 2002. She also quotes Jytte Klausen ("who knows Hirsi Ali") as saying that "She wasn’t forced into a marriage. She had an amicable relationship with her husband, as well as with the rest of her family. It was not true that she had to hide from her family for years." As far as I can see, the source of this quote is a telephone conversation that Haroon Saddiqui had with Klausen in May before penning his poisonous attack on Hirsi Ali in The Toronto Star. I don’t know how well Klausen "knows" Hirsi Ali, besides the fact that they have appeared at at least one seminar together in Sweden in 2003, but I do feel inclined to treat her statement with some scepticism.Alam also writes: "Practically all of her conclusions are based on her own ‘tortured’ experiences and observations of Islam". I can well imagine that if, as Hirsi Ali did, I worked as an interpreter in abortion clinics and refuges for battered women, then I might see the world through a jaundiced eye, but that does not remove the reality of those observations and experiences. One chapter entitled Four Women’s Lives gives the stage to others to tell their story. One of the strengths of Hirsi Ali’s book is that she does provide the source references to her claims – although Alam sneers that: "she provides little evidence to back up her claims that the Muslim woman is a caged virgin – sexualised, segregated, denied human rights – and that Islamic theology is responsible for this". Really, I wonder whether we’ve actually read the same book.But then, MRDA – Mandy Rice-Davies Applies. When it comes to facing unpalatable truths about aspects of one’s religion, Alam’s reaction and subsequently the review should come as no surprise. To paraphrase Mandy, "She would write that, wouldn’t she?" -

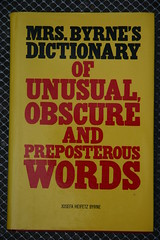

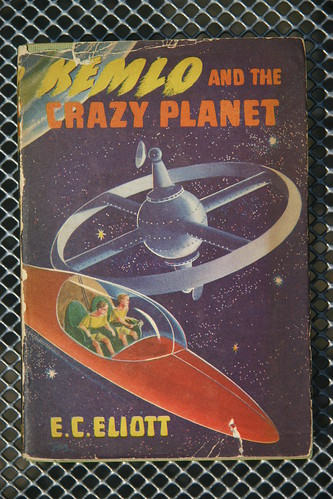

Book Fair in Bredevoort

Bredevoort is a small village in our neighbourhood. It’s the Dutch equivalent to Hay-on-Wye, being filled with more bookshops than you can shake a stick at. In addition, it has regular open-air book markets. There was one today, and it being a pleasant day, I cycled along to have a look.I struck lucky with two books. The first was a hardcover edition of Mrs. Byrne’s Dictionary of Unusual, Obscure and Preposterous Words. I’ve long had a paperback edition in my library, but it’s been well thumbed and showing the signs of being the worse for wear. To find a pristine hardcover edition was a joy. The longest word in it contains 1,913 letters (the chemical name for tryptophan synthetase A protein).The second was a children’s book: Kemlo and the Crazy Planet. I had several books from the Kemlo series as a child, but, alas, lost track of them during the course of the years. When I saw this book (still with its dustjacket) lying on a stall, I knew that I had to buy it instantly.The books were written by Reginald Alec Martin (alias E. C. Eliott) and were probably one of the factors that got me hooked on science and science fiction when still a very small boy. I’m very pleased with this find… -

What I Did Wrong

That’s the title of a new book by John Weir. Well, actually, it’s only his second book since the publication of The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket back in 1989. Eddie Socket was a brilliant debut by Weir – so good that I wound up having two copies of it in the library – having first bought the paperback edition, I tracked down a hardcover edition so that it would last longer.And how did I find out that Weir has published his second novel after a gap of 17 years? That’s the beauty of serendipity on the internet… The Mumpsimus blog had a chance mention of an article in The Village Voice by Edmund White on the "new gay fiction". Following the link and reading the article (because White usually has something interesting to say) unearthed the fact that Weir has a new book out on the streets. As a result, What I Did Wrong has gone onto my want list. -

A Time There Was…

I’ve just finished reading John Bridcut’s biography of Benjamin Britten: Britten’s Children.Simply superb!I have a nodding acquaintance with various parts of Britten’s work: Serenade, Prince of the Pagodas, Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, etc. Now, after reading this book I want to go back and listen with revitalised ears and to explore the rest of his music. Particularly Noyes Fludde, Death in Venice and the Turn of the Screw. -

Hugo Winners Meme

Nicholas, over at the From the Heart of Europe blog, brings the Hugo Winners meme to my attention. The Hugos are the annual awards given to the best writing in Science Fiction for the year. Nicholas has read every one of the novels on the list, and his version of the list, available here, contains links to his critiques of the award-winners. I’m not so thorough – the entries that I’ve read are in Bold.2005 Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, Susanna Clarke

2004 Paladin of Souls, Lois McMaster Bujold

2003 Hominids, Robert J. Sawyer

2002 American Gods, Neil Gaiman

2001 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, J. K. Rowling

2000 A Deepness in the Sky, Vernor Vinge

1999 To Say Nothing of the Dog, Connie Willis

1998 Forever Peace, Joe Haldeman

1997 Blue Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson

1996 The Diamond Age, Neal Stephenson

1995 Mirror Dance, Lois McMaster Bujold

1994 Green Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson

1993 Doomsday Book, Connie Willis

1993 A Fire Upon the Deep, Vernor Vinge

1992 Barrayar, Lois McMaster Bujold

1991 The Vor Game, Lois McMaster Bujold

1990 Hyperion, Dan Simmons

1989 Cyteen, C. J. Cherryh

1988 The Uplift War, David Brin

1987 Speaker for the Dead, Orson Scott Card

1986 Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card

1985 Neuromancer, William Gibson

1984 Startide Rising, David Brin

1983 Foundation’s Edge, Isaac Asimov

1982 Downbelow Station, C. J. Cherryh

1981 The Snow Queen, Joan D. Vinge

1980 The Fountains of Paradise, Arthur C. Clarke

1979 Dreamsnake, Vonda N. McIntyre

1978 Gateway, Frederik Pohl

1977 Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, Kate Wilhelm

1976 The Forever War, Joe Haldeman

1975 The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin

1974 Rendezvous with Rama, Arthur C. Clarke

1973 The Gods Themselves, Isaac Asimov

1972 To Your Scattered Bodies Go, Philip José Farmer

1971 Ringworld, Larry Niven

1970 The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin

1969 Stand on Zanzibar, John Brunner

1968 Lord of Light, Roger Zelazny

1967 The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, Robert A. Heinlein

1966 Dune, Frank Herbert

1966 "…And Call Me Conrad" (This Immortal), Roger Zelazny

1965 The Wanderer, Fritz Leiber

1964 "Here Gather the Stars" (Way Station), Clifford D. Simak

1963 The Man in the High Castle, Philip K. Dick

1962 Stranger in a Strange Land, Robert A. Heinlein

1961 A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter M., Miller Jr

1960 Starship Troopers, Robert A. Heinlein

1959 A Case of Conscience, James Blish

1958 The Big Time, Fritz Leiber

1956 Double Star, Robert A. Heinlein

1955 They’d Rather Be Right (The Forever Machine), Mark Clifton & Frank Riley

1954 (Retro-Hugo) Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

1953 The Demolished Man, Alfred Bester

1951 (Retro-Hugo) Farmer in the Sky, Robert A. Heinlein

1946 (Retro-Hugo) The Mule, Isaac Asimov (part II of Foundation and Empire)One of the things that strikes me, from looking at my list, is that it confirms that I used to read a lot more SF than I do now. And I have moved on from reading Heinlein, who became tiresome to me. I still look out for books by Le Guin, though.